Why Kitizen Science is Needed

Definitions and history

Definitions and history

First, a short definition of terms used on this page and elsewhere on the website. There are a lot of names for programs that sterilize unowned outdoor cats and return them to where they were trapped (trap-neuter-return, shelter-neuter-return, return to field, community cat programs). We use "spay/neuter program" because it is an all-inclusive and neutral term. There are also many names for unowned outdoor cats (feral cat, community cat, stray cat, working cat, barn cat). We have chosen to use "free-roaming cat" as the most all-inclusive and neutral term.

Depending on who you ask, the idea of using spay/neuter programs to control free-roaming cat populations in the United States started in the early 1990s in Newburyport, MA, Orlando, FL, or Washington, DC. The concept seeks to stabilize and decrease a free-roaming cat population by using surgical sterilization (removing the testicles or ovaries and uterus) to prevent new kitten births and allowing the adults to live out their life spans. This is an alternative to culling, the traditional animal control method of capturing unowned cats, impounding them to an animal shelter, and ultimately euthanizing them.

Effects of spay/neuter programs

There is broad public support for using spay/neuter programs instead of culling to manage free-roaming cat populations, and there is peer-reviewed research that these spay/neuter efforts can correlate with decreases in shelter intake, lower shelter euthanasia of cats, and reduced cat nuisance complaint calls. However, there is little evidence as to whether spay/neuter programs control or reduce the size of cat populations.

Those who are involved with spay/neuter programs believe that their work is reducing cat populations. It's easy to find people in cat welfare circles who can tell you about their personal experiences over years or decades of trapping cats and taking care of cat colonies while watching populations decline or disappear over time. Although these oral histories are compelling to cat advocates, personal stories aren't scientific evidence that spay/neuter programs can reduce cat populations.

Read about scientific evidence on the effects of spay/neuter programs.

Metrics and impact assessment

Metrics and impact assessment

The best policies and programs are those that are shown by data to be proven effective at doing the things they claim to do. Rigorously testing what works best helps a field move forward (and save more lives).

Most of the spay/neuter research published by veterinarians and animal welfare professionals focuses on the metric that is most important to cat lovers: reducing the deaths of cats. However, for those who oppose using spay/neuter programs and push for widespread culling of cats, reducing cat deaths is not the issue that matters to them. Metrics championed by cat advocates as proof that spay/neuter programs work - decreases in shelter intake, lower shelter euthanasia of cats, and reduced cat nuisance complaint calls – are often viewed by cat advocates as evidence for cat population decreases. Fewer cats entering animal shelters could mean that there are fewer free-roaming cats outdoors, or it could mean that a given shelter simply changed their intake policies.

The reduced intake of cats to animal shelters is an indirect metric of a decrease in free-roaming cat populations, as is a decrease in shelter euthanasia or cat-related complaint calls to animal control. Whereas this type of data is easy to obtain and track over time – and it's better to track these indirect metrics than nothing at all – there is a need for better tools for monitoring the direct metric of the number of cats on the outdoor landscape. Of the ways that one can conduct an impact assessment of a spay/neuter program, this is the most difficult metric to study. Few people in cat welfare and veterinary worlds know about methods to quantify populations of free-roaming animals. Wildlife researchers and population ecologists, however, have an array of methods to do so.

Veterinary medicine and population ecology

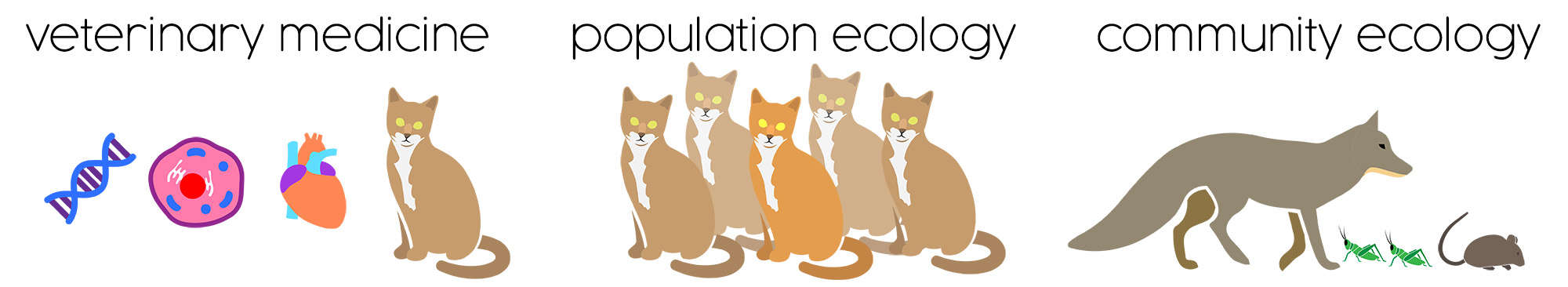

Is Kitizen Science using research methods from veterinary medicine? No. We're using methods from wildlife population ecology, a different field.

Veterinarians generally focus on individual-level biology: genetics, cellular biology, physiology, and an individual animal's health and welfare. Veterinary education includes some training in epidemiology – the study of disease in populations of animals – but this is mostly limited to meat safety in animal agriculture operations and controlling zoonotic diseases like rabies. Veterinarians are great at what they do and integral to the world of animal welfare, but they don't have the training to quantify and monitor population sizes of free-roaming animals.

Population ecologists are wildlife researchers that focus on groups of animals and the size and dynamics (changes in size) of a population. They can't diagnose an animal with a medical condition or provide treatment the way a veterinarian can, but a population ecologist can study questions that involve animal reproduction, behavior, migration, or adaptations to living near humans, such as, "How many offspring do coyotes produce in the suburbs of California versus the wilds of Alaska?"

Community ecologists go a step further and study how populations of many species interact together as a network. They explore questions such as, "What happens to coyote populations when there is a huge increase in mouse populations, and what effect will that have on grasshopper populations the following year?"

Collaborations to fix big issues

When spay/neuter organizations, veterinarians, and population ecologists work together, big things can happen and we can tackle complex issues together. Two such collaborations are already occurring.

The DC Cat Count was a collaboration between PetSmart Charities, The Humane Society of the United States, the Humane Rescue Alliance, the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, and the ASPCA. Together, these institutions conducted a large, complex three year study of the population dynamics of cats in Washington, DC, and the interconnected flow of cats between free-roaming, owned pets, and shelter animals. Results coming soon!

The Hayden Island Cat Project is a collaboration between the Feral Cat Coalition of Oregon and Portland Audubon. Together, they are conducting annual transect count surveys of an island neighborhood in Portland, Oregon to monitor the cat population and see if the island's spay/neuter program is reducing the number of cats.